Levels and modes of solidarity

The Solidarity Playbook has highlighted two dimensions of solidarity to consider to establish a common cause. The first dimension is identifying the levels of solidarity, or the ‘WHO and WHERE’. The second dimension is identifying the modes of solidarity, or the ‘HOW’.

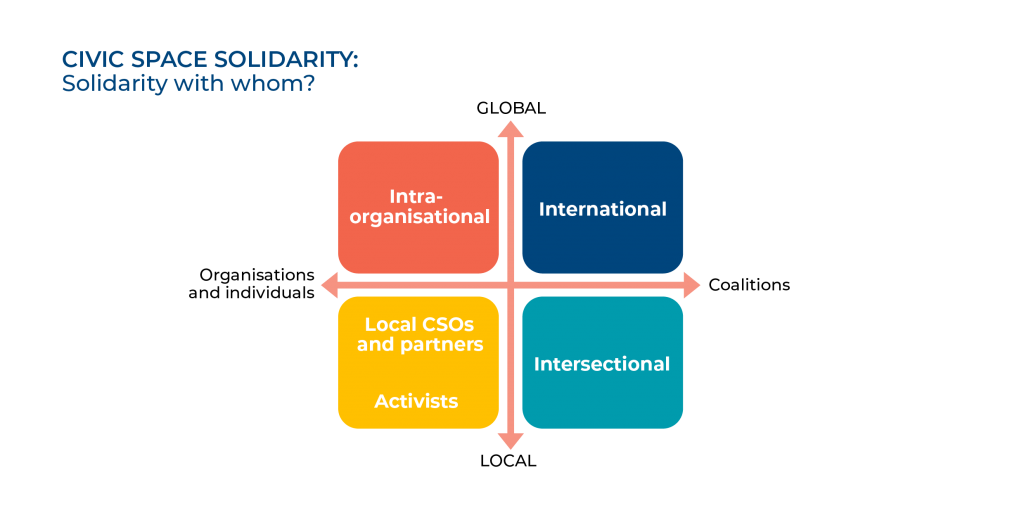

Levels of solidarity: Solidarity with whom and where?

Solidarity involves sharing values and building relationships with individuals and organisations with different ways of working or with different needs. This will depend on specific triggers that bring groups together – whether it is a direct attack on an organisation or a gradual shrinking of the operating environment for civil society, or a long-standing relationship that needs deepening or transforming.

With this in mind, we found four broad dimensions involved in the ‘with whom and where’ different organisations were working in solidarity. These dimensions demonstrate the different levels within which solidarity is demonstrated in practice:

Solidarity may be with formal or informal groups who are often at the forefront of direct attacks. They may be social movements, for example, or activists working on specific issues and needing support.

ICSOs can be large families of organisations each with different priorities, all with multiple departments. Several case studies show the importance of solidarity between different parts of an ICSO family and across the organisation itself, for example between the international secretariat and national offices.

Civic space, perhaps more than any other issue requires a coming together of civil society across a range of issues, for example humanitarian action with human rights. Intersectional solidarity therefore naturally involves coalition work. Though it can be situated globally or locally, we found that intersectional solidarity was more common at the national or subnational level.

International solidarity connects the national to the international. This could be linking local partners to international mechanisms, such as at the UN level, or connecting different national partners across a single issue, such as anti-terrorism or internet shutdowns.

It’s important to factor in that solidarity may be required at multiple levels. Solidarity at the international level, for example, can help raise global awareness to issues related to civic space for those at the national level; or build collaboration across borders, whilst solidarity with local partners could involve supporting protective measures at the same time. A multilevel approach to solidarity can act as a ‘pincer’ movement, creating pressure and support at different times.

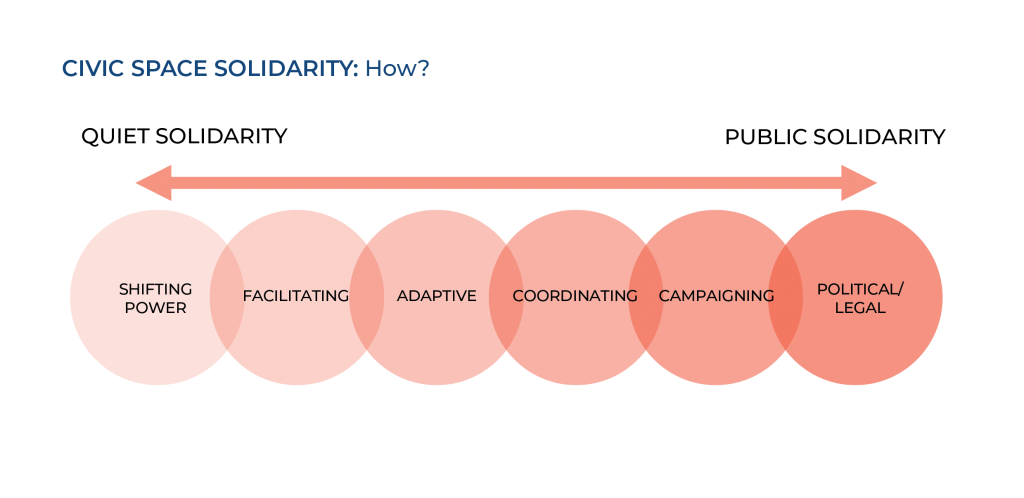

Modes of solidarity: How is solidarity demonstrated in practice?

There has been an assumption often made that ‘solidarity’ requires speaking out publicly about closing space. However, we found many ways of working in solidarity that were not public-facing, though none-the-less effective. In general, (though not exclusively) quiet solidarity was adopted in more closed and restricted (and risky) environments. Public solidarity was found where contexts either weren’t as closed, but were narrowing, at the national level, or at the international level when multiple organisations joined together to share risk, such as global campaigns and coalitions.

Modes of solidarity found in the Solidarity Playbook include:

Solidarity happens in many forms. In our review, we found that closing civic space can act as the catalyst to establish new relationships and ways of working with partners such that they have more control over decision-making and resources. As a mode of solidarity, this resulted in the local organisation being able to determine how and when they would work, and having adequate resources to continue to function, even in a highly closed and politicised civic space environment. In these cases, organisations had to address internal systems and/or negotiate with donors in order to address perceived risk. They also had to negotiate with local actors to determine the lead regarding what they want or need from ICSOs. Plan International adopted a ‘shift the power’ strategy with youth-led organisations in Latin America and found that it enabled discussions about a wider cultural change within the organisation more broadly.

Modes of solidarity are those that provide tools to partners on the ground. It might also involve facilitating access to international decision-makers, such as through UN processes. This would require an assessment of the needs and capacities of local groups, and bringing direct (often non-financial) resources to bear, which could include training or spaces in which to meet. It can also involve protecting activists and organisations. Helvetas provided an example of this through their work building capacity to engage with and facilitating access to UN human rights processes by groups at risk in a particular country, connecting them to CIVICUS, and providing safe spaces for local activists to meet and strategise. This mode of solidarity requires capacity for facilitation and convening on the ground, and high levels of trust between actors.

Modes of solidarity were generally adopted on an intra-organisational basis. For example this could entail a Secretariat or federation adapting expectations, requirements, resource flows or engagement in order to show solidarity to a national office, to ensure the work can continue, and to help keep some dimensions of civic space alive in that setting. It may also involve changing organisational strategies and adopting new procedures and risk management approaches. Adaptation has been a strategy adopted by ICSOs in our case studies, including Transparency International in Cambodia and ActionAid in Uganda, the latter as a result of a direct attack on the organisation.

Modes of solidarity can see an ICSO acting in a way that could host or create a coalition, or support a group of national or sub-national CSOs. This may involve more risk-taking on the part of one organisation, or bearing more resources, but could also involve a risk-sharing strategy across multiple organisations. VSO in Ethiopia, for example, hosted a secretariat for a national coalition for civil society, to help support the expansion of civic space collectively. This involved provision of resources from the international secretariat, and a greater level of risk bearing held at the national office in Ethiopia.

In solidarity involves creating a joined-up campaign across organisations on civic space. We identified several campaigns that united multiple groups at both the national and international level. In some cases, they were hosted and created by an ICSO, whilst in other cases ICSOs were part of these coalitions, or acted as allies. Campaigning tactics of course varied, from working on shifting CSO narratives in the public sphere, as the ‘It Works’ campaign in Poland did, where they highlighted through the media and campaigning the valuable work of CSOs; or the ‘#KeepItOn Campaign’ that unites groups around the world to protect access to digital spaces when governments seek to close them down.

Involves direct challenges to a government through legal or political means. Some coalitions, for example, chose to openly protest closing civic space actions by governments, while others chose to take the government to court through strategic litigation. Issues here included security risks for those on the ground, and threats to access for any regional or international groups involved. We found that this mode of solidarity is most effective when combined with other forms and mechanisms within a multilevel strategy. For example if space is closed at the national level, international actors can campaign to raise awareness at the international level (which also provides vital psychological support to those at risk), whilst facilitating provision of resources to local actors such as security training or legal support to those under direct attack, alongside engaging in political or diplomatic engagement whether publicly or behind closed doors. Case studies from Nicaragua and Malawi demonstrate the need for these combined modes of solidarity, including political and legal engagement, from international actors during times of conflict or political and civic strife.

In many of the case studies, we see civil society actors defending or creating space using multiple modes, and at times moving between these, depending on where opportunities for openings arise.